📓 Introduction to Big O Notation

Big O notation is an essential computer science concept — and probably the most important concept you'll learn in this course. We can use Big O to describe the overall performance of an algorithm. Big O is short for order of, which we can also think of as the algorithm's rate of growth, whether that rate of growth is the amount of time the algorithm takes or the space it takes up in memory. In other words, Big O is used both to measure the runtime of an algorithm (how long it takes to execute) and the space of an algorithm (how much space it takes in memory). Generally, the most common concern is Big O runtime but we'll also briefly touch on Big O space as well.

Generally, we use Big O to determine the worst-case scenario for an algorithm, though it can also be useful to determine the expected case if the worst-case scenario is very rare. Checking the best-case scenario is rarely useful. We'll discuss this further soon, but as you might guess, we have to anticipate problems as programmers, not just hope for the best. The worst case scenario is also known as the upper bound. The upper bound is the absolute most number of operations that an algorithm will need to take when it executes. So it's not quite accurate to think of Big O in terms of how long an algorithm takes to run but rather how many operations it will take to complete. A very fast machine will be able to do more operations per second, but even so, the more operations an algorithm runs, the longer it will take.

Ultimately, Big O answers a very simple question: can an algorithm scale up to deal with large data sets? The problems we solve at Epicodus usually deal with small data sets so it's rare that we'll even notice if an algorithm is inefficient. However, in the real world, companies like Google and New Relic are dealing with large datasets all the time. That's why it's common for Big O to come up in interviews, especially for back end and full-stack developers.

Without Big O notation, it's difficult to measure how efficient our algorithms are. And if we can't even tell if our algorithms are inherently fast or slow, we won't understand whether they are the right tools for the job at hand — or even if we're writing good code in the first place.

In this lesson, we will cover some of the most common Big O examples. There are more complex examples that are beyond the scope of this lesson but you won't see them as often in the real world. Note that we will mostly focus on each example in terms of runtime.

Remember that this is supposed to be an overview of key Big O concepts. You will not have a complete understanding of the topic by the end of this lesson. There are entire books on Big O notation. Consider this an introduction to the topic — and do further reading on your own if you wish to dive deeper.

O(1) Time

O(1) is constant time. That means that no matter how Big Our data set is, the algorithm will always take the same amount of time. Imagine we have the following function which returns the first element of an array:

function returnFirst(array) {

return array[0];

}

No matter how Big the data set is, returning the first item in the data set is trivial. It will always take the same amount of time.

Note that O(1) doesn't necessarily mean fast. It just means constant. It could still be something that takes a long time. For instance, imagine we have a very Big, heavy rocket that we want to send to the moon. It's a powerful rocket but it's also fairly slow. The benefit of this rocket is that no matter how much equipment we put in the storage of the rocket, it will take the same amount of time to get to the moon. We'd say that the time is constant even though it will take a long time to get to the moon.

In general, though, algorithms that use O(1) are very efficient. For instance, inserting a node at the beginning of a linked list is O(1) because it will always be the same regardless of how Big the linked list is. We will learn more about linked lists later in this course.

O(N) Time

O(N) is linear time. The larger a data set is, the longer an algorithm in O(N) time will take — but the increase in time will be constant.

A good example is a function that loops through a data set:

function doubledArray(array) {

let doubledArray = [];

array.forEach(function(element) {

doubledArray.push(element * 2);

});

return doubledArray;

}

In this example, we use a loop to double each element in an array. If array is very small, it won't take long for this function to run. However, the larger the array is, the longer it will take for the function to run — but it will take the same amount of time for each element in the array. So if it takes .000001 seconds for each iteration through the loop — it would take .000001 * 100 if the array has 100 elements and it would take .000001 * 100,000 if the array had 100,000 elements.

For that reason, we can portray the increase in time as linear:

As we can see from this chart, as the size of the dataset increases, so does the runtime — but the increase is linear.

Let's return to our example of the rocket. Let's say we have a rocket that's very fast, but the more stuff we load on it, the longer it takes to get to the moon — but the increase in time is constant.

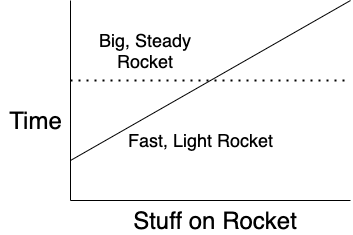

Let's compare the two using the graph below.

We have a Big, steady rocket which always takes the same amount of time to take cargo to the moon. Then we have a light, fast rocket which can get to the moon much faster — but only if it doesn't have too much cargo. At some point, if you add enough cargo to it, the fast rocket becomes slower than the Big, steady rocket — because it's not so light anymore.

Generally, while O(1) will be faster than O(N), it's important to realize that some things that are constant can still take a long time.

In an ideal world, our algorithms would never be more than O(N) in runtime. However, sometimes it's just not possible to write an algorithm that is that efficient.

O(N2) and O(2N) Time

Our rocket example is definitely oversimplified. If we actually added more cargo to a rocket, we'd also need more fuel to get the extra weight into space. There are probably lots of other factors we aren't accounting for as well. Let's say that for every extra item of cargo we add, we'll see an increase in time that is proportional to the square of the data set. In other words, for every extra piece of cargo we add, instead of seeing an increase that's linear, we'd see an increase that is proportional to the square. This can be described as O(N2) and is known as quadratic time complexity.

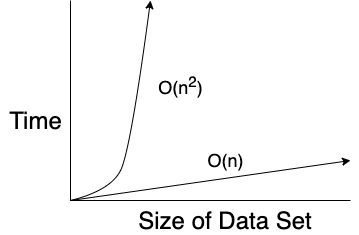

The chart looks something like this:

As we can see here, O(N2) takes a lot longer as a data set gets Bigger. And this kind of runtime is actually not uncommon as you might think. A prime example of O(N2) is using a nested loop with a data set.

For instance, if we were trying to find duplicate values in an array, we might be tempted to loop through the array and then loop through each element again to see if there are any duplicates:

function findDupes(array) {

let dupeArray = [];

for (let i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

for (let j = 0; j < array.length; j++) {

if ((array[i] === array[j]) & ((j - i) > 0)) {

dupeArray.push(array[i]);

}

}

}

return dupeArray;

}

The algorithm above uses a nested loop to compare every element in the array against itself to determine if it's a duplicate. So the inner loop looks at each element for every element in the outer loop. If the values are the same — and the value of the index in the outer loop is greater than the value of the index in the inner loop (because otherwise, we'd double count duplicates), the element will be pushed into dupeArray. The algorithm has quadratic time complexity which makes it quite slow.

Obviously, this is a terrible algorithm. Why not improve it by having the inner loop search only from the index of the outer loop onward? Well, that would improve the algorithm somewhat. It would go from being O(N2) to O(N2/2).

Isn't that a lot faster once we divide the overall value of N by 2? Not really. It is a slightly better algorithm but it is still quadratic time. When computing the runtime using Big O, we should drop the constants. So O(2N2) and O(N2/2) or even O(5N2) are all effectively the same — they can be seen as simply O(N2).

Ultimately, there are more efficient ways to find duplicates in an array — and we should generally try to avoid quadratic time in favor of linear time. However, when we get to learning algorithms later in this course, we'll learn a few that have quadratic time complexity including bubble, selection, and insertion sort algorithms. Needless to say, you won't actually use these algorithms much in the real world because there are more efficient options.

What about O(2N) time? This is known as exponential time and is even more inefficient than quadratic time. In an algorithm using exponential complexity, the number of operations needed doubles for every item added to a data set. In general, exponential time should be avoided if possible. An example of exponential time is recursively calculating Fibonacci numbers:

function calculateFibonacciNumbers(number) {

if (number <= 1) {

return number;

}

return calculateFibonacciNumbers(number-1) + calculateFibonacciNumbers(number-2);

};

The key thing that demonstrates that this is exponential is in the return statement: calculateFibonacciNumbers() has to be called twice! So each time calculateFibonacciNumbers() is called and the conditional isn't met ((number <= 1)), the function needs to recursively call itself twice.

As you can see here, a recursive function that needs to call itself twice is an indicator that we are probably looking at an algorithm that uses exponential time.

This function also uses exponential space as well. That's because recursive functions use a call stack — and the Bigger the call stack, the more memory the function calls will take. Whenever we write an algorithm that uses recursion, we need to think about Big O space as well as time. That's because the call stack will grow each time the function is called — and the call stack will not be resolved until each recursive call is resolved as well.

O(log(N)) and O(Nlog(N)) Time

O(log(N)) is known as logarithmic time while O(Nlog(N) is known as linear logarithmic time. Considering that most of us probably don't deal with logarithms much (if at all), we'll start by reviewing what a logarithm is. A logarithm is simply the power a number must have to equal another number.

log 100 is 2 because 102 is 100. When log is written by itself, we are talking about powers of 10.

log3 9 is 2 because 32 is 9. The 3 denotes that we are talking about powers of 3 instead of 10.

Fortunately, there's often an easy way to see whether an algorithm uses logarithmic time without being an expert on logarithms. If we see an algorithm where the size of the data set is halved each time, it is likely using O(log(N)). Examples of this include a binary search algorithm, where half of the elements in a collection are removed after each iteration, and searching a balanced binary search tree. We will learn more about both the binary search algorithm and binary search trees in future lessons, so don't worry about them now.

Meanwhile, merge sort and quick sort algorithms both use linear logarithmic time (O(Nlog(N)). They are considered among the most efficient algorithms for sorting and are commonly used in the real world. We will learn both later in the course.

By the way, why aren't we dropping the first N in Nlog(N) here? Isn't that a constant? Well, we can't actually remove the N. This is linear time multiplied by logarithmic time. It's not the same as 2log(N) — which means we can't drop that first N.

So how efficient are algorithms that use logarithmic and linear logarithmic complexity? They are less efficient than O(N) — but they are considerably more efficient than O(N2) and O(2N) time.

Summary

In this lesson, we've learned about the following Big O runtimes (ordered below from most to least efficient):

Efficient

- O(1): Constant time

- O(log(N)): Logarithmic time

- O(N): Linear time

Less Efficient

- O(Nlog(N)): Linear logarithmic time

Inefficient

- O(N2): Quadratic time

- O(2N): Exponential time

Note that there are many other Big O runtimes as well — but you probably won't have to worry about them unless you pursue a Computer Science degree or really dive deeper into back end programming.

Further Resources

We recommend further exploration on your own, especially if this is a topic that you are interested in — or if you still find that you are confused even after going through this lesson a few times. We will be touching on Big O complexity regularly throughout our computer science curriculum as well, so the topic should gradually become more familiar over time.

Here are a few resources to look into:

- Big O Notation Video with Gayle Laakmann McDowell: McDowell is author of Cracking the Coding Interview. This is an excellent resource on Big O notation and required viewing.

- What is Big O Notation?: This blog has a series of articles on Big O. (To get to the next article in the series, scroll to the bottom of the page.)

- Big O Cheatsheet: This cheatsheet gives an overview of the complexity of different Big O runtimes — as well as the Big O complexity of various algorithmic operations. The information on specific algorithms is a good reference to return to after future lessons as we cover various algorithms and concepts.

In the next lesson, we'll practice identifying the Big O notation of various algorithms.