📓 Depth First Algorithms

In the last lesson, we covered depth-first search and breadth-first search approaches. There are a lot of benefits of using these algorithms. We could determine the reachability between two nodes or we could determine the shortest path between two nodes, just to name a few use cases.

We'll start with the depth-first algorithm because it is a bit easier to implement. To actually use a TDD approach and test our algorithms in a graph, we are going to need to code that graph first. We will add this graph to our test file.

To keep things separated out, we are going to create a new test file called dfs.test.js and run all tests related to our depth-first search there. Here is the starter code which includes a graph.

import Graph from '../src/graph.js';

describe('depth-first search', () => {

let graph = new Graph();

graph.addNode("Jasmine");

graph.addNode("Ada");

graph.addNode("Lydia");

graph.addNode("Rose");

graph.addNode("Dylan");

graph.addNode("Allison");

graph.addNode("Thomas");

graph.addNode("Sarah");

graph.createEdge("Jasmine", "Ada");

graph.createEdge("Jasmine", "Lydia");

graph.createEdge("Jasmine", "Rose");

graph.createEdge("Ada", "Dylan");

graph.createEdge("Lydia", "Ada");

graph.createEdge("Dylan", "Allison");

graph.createEdge("Lydia", "Thomas");

});

Note that we don't put the graph in a beforeEach() or afterEach() block. We aren't actually going to modify this graph, just traverse it, so there's no need to re-instantiate it before or after every single test.

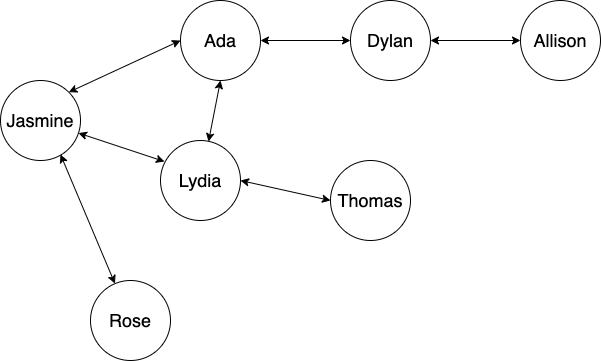

Next, let's include a visual representation of the coded graph above. It's the same one we were using in the last lesson.

There is one small but key difference about our graph that is not included in our illustration. We've also added Sarah, a node that isn't connected to anyone in the graph. We'll need this for one of our tests — which we'll cover in a moment.

Our DFS will just check to see if a node is reachable from another node. In this case, we just want to see if we can reach Thomas via Jasmine. While it's obvious from our graph that all its nodes are reachable from each other (except for Sarah), in a real-world application, that might not be the case.

Let's write our first test. We'll call our method Graph.prototype.depthFirstReachable() and it will return a boolean. The reason for the wordy name is because we'll write a method called Graph.prototype.breadthFirstReachable() in the next lesson that does the exact same thing as this method — but with a different algorithm.

The simplest implementation of our Graph.prototype.depthFirstReachable() method is to return false if a potential node doesn't even exist in the graph. For the sake of brevity, we'll code two tests right now: one to check the starting node, one to check the target node. Here are the tests:

...

test('should return false if the target node doe not exist', () => {

expect(graph.depthFirstReachable("Jasmine", "Albert")).toEqual(false);

});

test('should return false if the starting node doe not exist', () => {

expect(graph.depthFirstReachable("Albert", "Thomas")).toEqual(false);

});

...

Now let's get these tests passing:

...

depthFirstReachable(startingNode, targetNode) {

if ((!this.adjacencyList.has(startingNode)) || (!this.adjacencyList.has(targetNode))) {

return false;

}

}

...

Our method will take two arguments: the first, a startingNode, is the node we want to start from. The second is the targetNode, which is the node we want to find. In an undirected graph, these arguments could be interchangeable. In a directed graph, on the other hand, the order would matter.

Our method just checks to see if both nodes exist in the adjacency list. If one or the other doesn't exist, they obviously aren't reachable. Why go to the trouble of doing a DFS, which could be computationally intensive with a big graph, when values don't even exist? Because our adjacency list is a Map, it is super-fast to do this lookup. Meanwhile, doing a DFS to search the whole graph — only to tell us the same thing — would be very inefficient.

Next, let's get to the fun stuff. We will check to see if a direct friend of Jasmine is reachable.

Here's the test:

...

test('should check if the first friend in the adjacency list is reachable', () => {

expect(graph.depthFirstReachable("Jasmine", "Ada")).toEqual(true);

});

...

Here's the thing. To get this test passing, we have to write most of the algorithm!

Now the code:

depthFirstReachable(startingNode, targetNode) {

if ((!this.adjacencyList.has(startingNode)) || (!this.adjacencyList.has(targetNode))) {

return false;

}

let stack = [startingNode];

let traversedNodes = new Set();

while (stack.length) {

const currentNode = stack.shift();

if (currentNode === targetNode) {

return true;

} else {

traversedNodes.add(currentNode);

const adjacencyList = this.adjacencyList.get(currentNode);

adjacencyList.forEach(function(node) {

if (!traversedNodes.has(node)) {

stack.unshift(node);

}

});

}

}

}

Let's focus on just the new code — which is our actual DFS algorithm:

...

let stack = [startingNode];

let traversedNodes = new Set();

while (stack.length) {

const currentNode = stack.shift();

if (currentNode === targetNode) {

return true;

} else {

traversedNodes.add(currentNode);

const adjacencyList = this.adjacencyList.get(currentNode);

adjacencyList.forEach(function(node) {

if (!traversedNodes.has(node)) {

stack.unshift(node);

}

});

}

}

...

First, we need to create our stack:

let stack = [startingNode];

It's an array with the startingNode as its only element.

Next, we also need some way to flag the nodes that have been traversed. We don't want this to be a property on the node itself because this flag is temporary — we don't want it to persist once the method is finished running.

let traversedNodes = new Set();

This is a perfect use case for a Set. We don't want there to be duplicate values — we just want to know whether a node has been traversed or not. And looking up whether a value in a Set is super-fast — so it won't take too much time. Remember, hash table lookup is O(1) constant time — and a Set uses a hash table under the hood.

At this point, we have collections to store a stack as well as a set of traversed nodes. We are ready to start looping!

In general, when looping through a stack or a queue that will eventually be empty, we can just iterate until the collection's length is zero. At that point, we know we've checked every value in the stack or queue.

That's exactly what we do here:

while (stack.length)

This just states that we should loop through the stack until it is empty. Once the length of the stack becomes zero, stack.length is falsy — and the loop will end.

Next, we need to take the first element from the stack:

const currentNode = stack.shift();

Array.prototype.shift() is a destructive method — that means that we aren't just grabbing the value of the first element in our stack — we are also removing it from the array. This is the currentNode that we are examining. It is a const because the variable itself never changes — it falls out of scope each time through the loop and is created anew.

Next, we have a conditional that checks to see if the currentNode === targetNode.

if (currentNode === targetNode) {

return true;

}

If they are equal, we've found the target node! The target node is reachable from the starting node — and we can return true.

If it isn't, we have more work to do. Here's the code in our else statement:

...

else {

traversedNodes.add(currentNode);

const adjacencyList = this.adjacencyList.get(currentNode);

adjacencyList.forEach(function(node) {

if (!traversedNodes.has(node)) {

stack.unshift(node);

}

});

}

...

First, we need to "flag" our node to show that it's been traversed:

traversedNodes.add(currentNode);

Here, we use the Set.prototype.add() method to add the currentNode to traversedNodes. This way, when we need to look up whether the node has been traversed or not, we'll see that the currentNode has been added. The first time through the loop, this will be the startingNode — also known as Jasmine.

Next, we need to find the adjacency list for the current node. In Jasmine's case, the list is a Set that includes Ada, Lydia, and Rose.

Once we've gotten the adjacency list, we are ready to add it to the stack. To do that, we iterate through the adjacency list, first checking each node in the adjacency list to see if it's in the traversed array — and then adding that node to the top of the stack with Array.prototype.unshift(), which adds an element to the beginning of an array. This will loop through the entire adjacency list, updating our stack. After the loop is done, our stack will look like this:

["Rose", "Lydia", "Ada"]

Because stack.length has three elements, it's truthy so the loop continues. Due to the following line const currentNode = stack.shift();, Rose is taken off the top of the stack and becomes the currentNode. Then the entire process continues — Rose is added to the list of traversedNodes and then her adjacency list is added to the stack and so on. Eventually, our DFS will find Ada and recognize that it's equal to the targetNode, meaning the method will return true.

If we update our test to look for Thomas instead of Ada, it will pass. As we can see, in order to find Ada, we had to write an algorithm that would also find Thomas — or anyone else in the graph.

There is one more thing we need to do. What about a node that exists but isn't reachable? That's why we added a node for Sarah. This node isn't connected to any other node in the graph — but it's still part of the graph, which means our initial conditional won't return false.

Here's the test:

...

test('should return false if the target node can not be reached from the starting node', () => {

expect(graph.depthFirstReachable("Jasmine", "Sarah")).toEqual(false);

});

...

Fortunately, getting this test passing is easy. At some point, stack.length is going to be falsy (because it's zero). At that point, we know that we've traversed every node in the graph that is reachable from the starting node. So if we've traversed the entire graph and we still haven't found the node we are looking for, we know it's not reachable. Here's the updated code:

depthFirstReachable(startingNode, targetNode) {

if ((!this.adjacencyList.has(startingNode)) || (!this.adjacencyList.has(targetNode))) {

return false;

}

let stack = [startingNode];

let traversedNodes = new Set();

while (stack.length) {

const currentNode = stack.shift();

if (currentNode === targetNode) {

return true;

} else {

traversedNodes.add(currentNode);

const adjacencyList = this.adjacencyList.get(currentNode);

adjacencyList.forEach(function(node) {

if (!traversedNodes.has(node)) {

stack.unshift(node);

}

});

}

}

return false;

}

This is our entire method. All we added is the return false; outside the while loop. As we can see here, we have a nested loop. The Big O of this particular algorithm is something akin to O(AB) — though that's not quite accurate because the B (the adjacency list for each node) is always changing — A (the stack itself) is always changing, too. It should be clear why that initial condition is even more helpful now. Searching the entire graph to determine that a node isn't reachable is a big task — best to check if one of the nodes doesn't exist in the first place.

At this point, if you are feeling any confusion about how this algorithm works (and it's very understandable if you are), the next step is to intentionally break one of the tests and get into Jest's debug mode so you can step through the method and watch how variables change. The GIF below shows this — all the relevant variables have been added to Watch in the left-hand pane. This loop runs until the algorithm discovers that the Thomas node is, in fact, reachable from the Jasmine node.

It can also be useful to look at what would happen if we didn't flag traversed nodes. In other words, if our code looked like this instead:

// This will not work! It will lead to infinite loops because we aren't flagging traversed nodes.

depthFirstReachable(startingNode, targetNode) {

if ((!this.adjacencyList.has(startingNode)) || (!this.adjacencyList.has(targetNode))) {

return false;

}

let stack = [startingNode];

while (stack.length) {

const currentNode = stack.shift();

if (currentNode === targetNode) {

return true;

} else {

const adjacencyList = this.adjacencyList.get(currentNode);

adjacencyList.forEach(function(node) {

stack.unshift(node);

});

}

}

return false;

}

Take a look at what happens when we do this:

We bounce back and forth between Jasmine and Rose because Rose is a friend of Jasmine and Jasmine is a friend of Rose back and forth forever and ever. A truly beautiful friendship! But we don't want this in our code.

So that is a depth-first search algorithm in a nutshell. We use a stack to search through each branch. In this lesson, we just focused on finding whether a node is reachable. You will get a chance to practice some other implementations soon as well.