📓 2.3.0.7 Making API Calls with JavaScript

Over the last several lessons, we've learned quite a bit about API calls to third-party APIs. We've learned what they are and how to make an API call using Postman. We also took a more in-depth look at working with and parsing JSON. The skills we've covered so far are applicable for working with APIs no matter what programming language you use. Whether you are writing in Ruby, JavaScript, C#, or another language, there are tools for making and receiving requests and then parsing JSON or any other type of data the API returns.

Now we are ready to build out a JavaScript application that will make an API call. There are many different ways to make an API call, ranging from using Web APIs to JavaScript libraries like jQuery (a library for DOM manipulation and traversal). There are also many JavaScript tools for handling asynchrony that vastly simplify making API calls. In this lesson, we'll learn how to use the XMLHttpRequest object (a Web API) to make an API call. Then in the two lessons that follow, we'll add error handling and learn how to manage our API key.

In later lessons, we will rewrite our code to make our API call in different ways. In the process, we'll also learn different tools for working with asynchronous code. After all, APIs are asynchronous. While we will only be learning how to apply async tools to API calls in this section, the async tools we learn can also be used for other asynchronous JavaScript operations as well.

However, we're not quite ready to jump off the async deep end just yet. We're going to start by learning how to make an API call the old-fashioned way with an XMLHttpRequest object. Why? The old-fashioned way of making an API call is what all other tools are built on top of, like jQuery's AJAX and the Fetch API (another Web API). In this course section, we'll learn how to use the Fetch API, but not jQuery's AJAX.

So while you may not be using XMLHttpRequest for this section's independent project (you can if you want!), you will have a better understanding of how tools like Fetch work when we actually use them later in this section.

Making an API Call in JavaScript

We will not include all the code for building out a complete webpack environment in this lesson. However, we'll share a repository at the end of this 3-part walkthrough with all of the code to make an API call in a fully functioning webpack environment. If you decide to code along with these next three lessons, make sure to include a webpack environment.

The next lesson covers how to protect your API key, so if you are coding along with this lesson, do not make any commits or push to a remote repository until you've completed the next lesson!

Note that because we aren't testing, we don't need a __tests__ directory. For now, we also don't need a js directory. All of our JS code in this lesson will be in index.js — the same naming convention we've been using with webpack projects. So for this walkthrough, we really just need to look at two files: index.html and index.js.

Let's start with the HTML:

<html lang="en-US">

<head>

<title>Weather</title>

</head>

<body>

<div class="container">

<h1>Get Weather Conditions From Anywhere!</h1>

<p>To get the current weather conditions for a location, please enter the city name or the city and state separated by a comma. Here are three examples:</p>

<pre>

Portland

Atlanta, Georgia

cairo

</pre>

<form>

<label for="location">Enter a location:</label>

<input id="location" type="text" name="location">

<button type="submit" class="btn-success" id="weatherLocation">Get Current Temperature and Humidity</button>

</form>

<p id="showResponse"></p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

We have instructions and a simple input for a location. We also have a P tag for showing the API response, which will be the temperature and the humidity, or an error message.

To style our HTML, we're using two Bootstrap classes: container and btn-success.

Now let's look at the code for the API call:

import 'bootstrap';

import 'bootstrap/dist/css/bootstrap.min.css';

import './css/styles.css';

// Business Logic

function getWeather(city) {

let request = new XMLHttpRequest();

const url = `http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=${city}&appid=[YOUR-API-KEY-HERE]`;

request.addEventListener("loadend", function() {

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

});

request.open("GET", url, true);

request.send();

}

// UI Logic

function printElements(apiResponse, city) {

document.querySelector('#showResponse').innerText = `The humidity in ${city} is ${apiResponse.main.humidity}%.

The temperature in Kelvins is ${apiResponse.main.temp} degrees.`;

}

function handleFormSubmission(event) {

event.preventDefault();

const city = document.querySelector('#location').value;

document.querySelector('#location').value = null;

getWeather(city);

}

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

document.querySelector('form').addEventListener("submit", handleFormSubmission);

});

Our JS is separated between business logic and user interface logic. All of the code should look familiar to you, except for the code inside the getWeather function.

Let's review all of the JavaScript by the order in which it runs. Starting at the bottom, we have two very familiar event listeners:

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

document.querySelector('form').addEventListener("submit", handleFormSubmission);

});

For the form 'submit' event listener, we pass in the function handleFormSubmission as a callback, to be called when the form is submitted. Remember that a callback function is a function that's passed into another function as an argument, to be used at a later time.

Next, in the handleFormSubmission function we do a few things:

- We prevent the default behavior of the form submission.

- We get the value from the form input and save it in a variable called

city - Then we call the function

getWeatherwith thecityas an argument;getWeatherwill handle making our API call to get the current weather data for the user-inputted city.

function handleFormSubmission(event) {

event.preventDefault();

const city = document.querySelector('#location').value;

document.querySelector('#location').value = null;

getWeather(city);

}

The function getWeather contains new and unfamiliar code. Take note that it is a part of our Business Logic, because it doesn't access or alter the DOM. Let's review this new code:

function getWeather(city) {

let request = new XMLHttpRequest();

const url = `http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=${city}&appid=[YOUR-API-KEY-HERE]`;

request.addEventListener("loadend", function() {

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

});

request.open("GET", url, true);

request.send();

}

This is the code that handles creating our API call: making a request, sending it, and handling the response. We'll break down this new code line by line.

First, we use the constructor of the XMLHttpRequest object (XHR for short) to create a new instance of it; we save this instance in a variable called request:

let request = new XMLHttpRequest();

The name XMLHttpRequest is a bit misleading. These objects are used to interact with servers — exactly what we want to do with API calls. They are not specific to XML requests. As we mentioned before, XML is one relatively common data format that APIs use to send data. However, JSON is much more common these days, and XMLHttpRequest objects can be used with JSON and other types of data as well, not just XML.

Next, we save the URL for our API call in a variable called url:

const url = `http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=${city}&appid=[YOUR-API-KEY-HERE]`;

Our URL string is a template literal with an embedded expression ${city}, so the value the user inputs into the form is passed directly into our URL string via our city variable.

Saving the request URL in a variable isn't necessary, but it makes our code a bit easier to read. Why? We'll use this url as one of three arguments passed into the following method later on: request.open("GET", url, true);. If we directly include the URL as the second argument, it makes our code a bit harder to read, like so: request.open("GET", http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=${city}&appid=[YOUR-API-KEY-HERE], true);.

Note that you'll need to put your own API key in [YOUR-API-KEY-HERE] for the code to work correctly. If you are coding along with this lesson, go ahead and add your API key now, but do not commit your code until you learn how to protect your API key in the next lesson.

Next, we set up an event listener that listens for when our API call is complete:

request.addEventListener("loadend", function() {

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

});

To do this, we set up an event listener for the XMLHttpRequest object's event called "loadend". The "loadend" event will fire when a request (API call) has been completed, whether or not it was successful.

Just like with other event listeners, the second argument is the callback function that will run when the corresponding event happens. So, when our API call is finished, this callback function will run:

function() {

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

}

This callback function does three things:

- Parse the API response

- Check if the API call was successful

- And if it was, call a function to print the data we received from the API

Let's run through each line of this callback function individually. First, we run the following line of code:

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

Starting with this.responseText, this represents our request object, and responseText is a property of XMLHttpRequest objects that contains the information sent from the API. This could be the weather data or an error message. Either way, the responseText property is automatically populated once a response is received from an API server.

We parse this.responseText with JavaScript's built-in JSON.parse() method. This ensures that the data is properly formatted as JSON data. Otherwise, our code won't recognize the data as JSON and we'll get an error when we try to use dot notation to get data from it. The JSON.parse() method is essential for working with APIs. As we mentioned in a previous lesson, other programming languages also have methods for parsing JSON.

Next, we use branching to determine if the HTTP status code of the API response is equal to 200.

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

status is also a property of XMLHttpRequest objects, and its job is to log the HTTP status code of the API call response.

Why does this.status === 200 need to be part of our conditional? Well, the "loadend" event fires when the API call is complete, but it doesn't take into account whether the API call was successful or returned an error. In the last lesson, we learned that a 200 response indicates a successful API call. So, this conditional states that the API call must be successful before our code processes that data.

If our API call is successful, we call the printElements function to handle printing the API response data to the webpage.

printElements(response, city);

We need to be sure to pass in the response from the API, as well as the user-inputted city so that our printElements can handle displaying all of that information.

Now let's take a look at the printElements function:

function printElements(apiResponse, city) {

document.querySelector('#showResponse').innerText = `The humidity in ${city} is ${apiResponse.main.humidity}%.

The temperature in Kelvins is ${apiResponse.main.temp} degrees.`;

}

As we can see, the printElements function prints the weather data to our webpage. Here, too, we use template literals to add variables directly to strings.

To access the weather data, we access properties within the apiResponse parameter, which represents the response object from the API.

Take note that how the data is structured in the API response object always varies from API to API. That's why it's so important to test API calls in Postman and practice parsing JSON and accessing the data you want.

Let's return to the getWeather function, because we're not done covering the code inside of it! Let's take another look at the entire function:

function getWeather(city) {

let request = new XMLHttpRequest();

const url = `http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=${city}&appid=[YOUR-API-KEY-HERE]`;

request.addEventListener("loadend", function() {

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

});

// We've covered everything except for the two lines below!

request.open("GET", url, true);

request.send();

}

By the time we've arrived at the last two lines of code in the getWeather function, we've done a few things:

- We've created a new

XMLHttpRequestobject saved in therequestvariable. - We've created our request URL with the city data and API key.

- We've created an event listener for the

"loadend"event to fire when the API call has finished in order to process the API's response.

But we haven't actually sent our request yet! Well, that's what these last two lines of code do: they open and send the request.

request.open("GET", url, true);

request.send();

The XMLHttpRequest.open() method takes three arguments:

- The method of the request (in this case

GET) - The request URL (which we stored in a variable called

url) - A boolean for whether the request should be asynchronous or not.

We always want the request to be async, because we don't want the browser to freeze up for our users! For the API calls we make in this section, these three arguments will almost always be the same — the only exception will be if you make a "POST" or other type of request instead of "GET", though it's not expected that you will in this course section.

Once we've opened the request, we send it. It's at this point that we wait for the API to return a response. Once it does, our callback function attached to the "loadend" event will run. Then, if our API call is successful, our printElements() function will be run.

More About XHR Objects

Let's go into a bit more detail about XMLHttpRequest objects. We can see exactly what properties an XMLHttpRequest object has by adding a breakpoint inside our conditional and then running the code in the browser. (You don't need to do this right now — it's fine to just look at the image below — but we recommend taking a closer look at an XMLHttpRequest object at some point.)

request.addEventListener("loadend", function() {

debugger;

const response = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

if (this.status === 200) {

printElements(response, city);

}

});

Adding a breakpoint from the Sources tab is better than adding a debugger; statement; the code snippet above just shows where the breakpoint should go.

When we're paused in the debugger, we can then go to the DevTools console and examine this:

> this;

XMLHttpRequest� {readyState: 4, timeout: 0, withCredentials: false, upload: XMLHttpRequestUpload, onreadystatechange: ƒ, …}

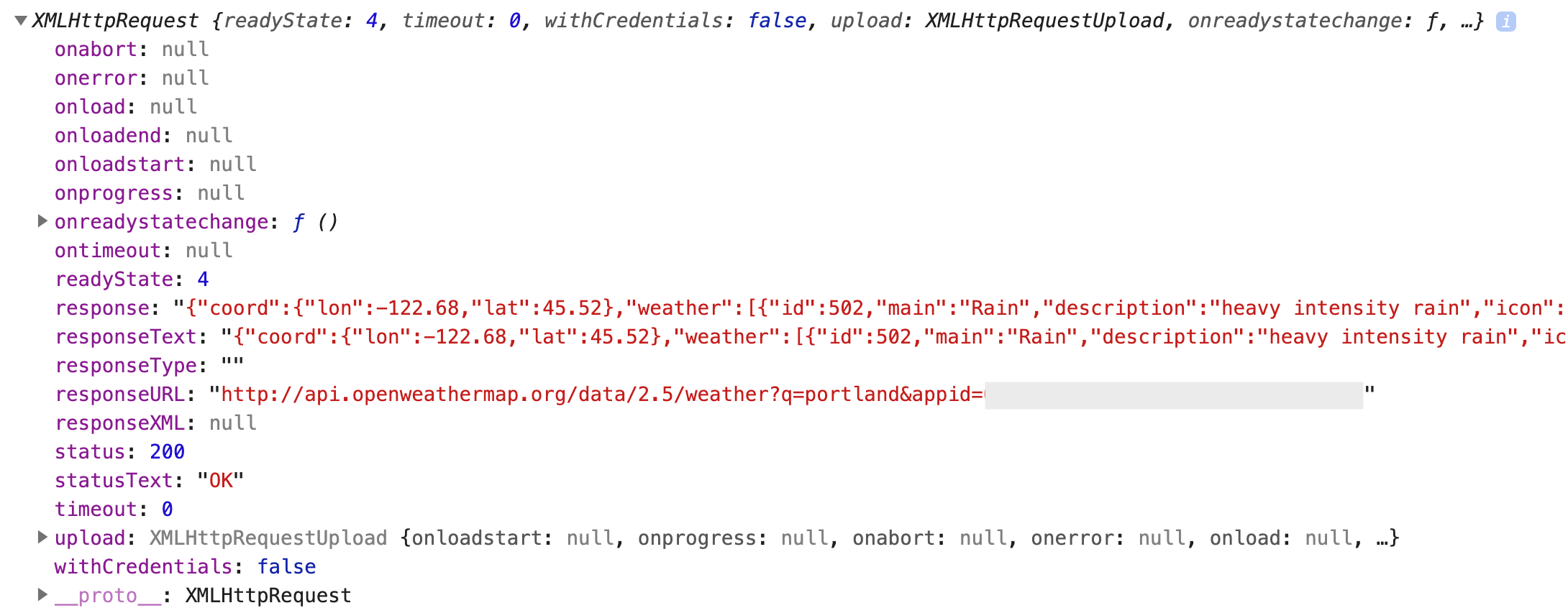

If we expand the XMLHttpRequest object in the DevTools console, it will look something like this:

We cropped this image — there's much more listed for both the response and responseText properties. As you can see, an XMLHttpRequest object has a lot of functionality. You don't need to worry about most of these properties right now. However, there are a few that will be helpful during this section:

responseText: We've already discussed this one. It includes the text of the API response. However, you won't be able to access the data inside this property with object property accessors until you parse it withJSON.parse(). (There's also aresponseproperty which has the same data, but this data may not be a string. To optionally learn more, visit the docs.)status: The status is the HTTP status code of the API response. A 200 means it was successful. There are many other codes such as 404 not found and so on. We will use thestatusin a future lesson.statusText: We'll see here that it's "OK". That's standard with a 200 status code. It means we are good to go! However, if something went wrong, this is where we might get a more detailed error message such as "not found" or "not authorized."

readyState

If we look inside of an XMLHttpRequest object, we'll also see a property called readyState. In the above image, readyState is is set to 4. While we won't use the readyState property, understanding it can help us better understand XMLHttpRequest objects.

The readyState property is always set to a number, and each number represents a different state that our XMLHttpRequest object can be in.

Check out the image below from MDN's reference on XMLHttpRequest.readyState. As we can see, XMLHttpRequest objects have five states they can be in. (Take note that an "XMHttpRequest client" is simply an instance of that object type.)

This table shows the states, 0 through 4, that an XMLHttpRequest object can be in

Each state describes a step in the process of making an API call using the XMLHttpRequest object. Once we get to 4, "DONE", we know that the API call has been completed.

To visualize the change in readyState as we make an API call in our weather app, we can set up an event listener for the "readystatechange" event, and log this.readState inside of it.

function getWeather(city) {

let request = new XMLHttpRequest();

...

request.addEventListener("readystatechange", function() {

console.log(this.readyState);

});

}

Doing so is completely optional, and we won't include this event listener in the example repo.

Summary

In this lesson we learned how to create an API call using an XMLHttpRequest object, and how to parse the API response into JSON so that we can access the data. We handled making the asynchronous request using the "loadend" event listener that fires when the API call has completed (with or without error).

Up next, we'll learn how to protect our API key(s), then we'll add error handling to our OpenWeather app.