📓 1.2.2.12 Event Handler Properties in a Project: Using window.onload

So far we've been practicing new code and concepts using the DevTools console. We've learned how to:

- Access the DOM.

- Manipulate DOM element attributes.

- Handle events with event handler properties.

It's important to feel comfortable with the DevTools console, because this is one of the quickest ways you can try out JavaScript and work with Web APIs! However, in this lesson we'll shift gears and learn how to incorporate the new code we've learned into our project's JS file.

In the process, we'll learn about a new event handler property for the window object that makes our JS code wait to be run until our webpage and all of its resources have been loaded: window.onload. Soon, we'll learn why this is important.

Adding Event Handling to a Project's JS File

All of the code that we've written in the DevTools console can be added directly to our project's JS file. However, there are different ways to organize your code. Let's work through some examples. You are welcome to code along with this lesson, or just read through it. In the next lesson, we'll practice the concepts covered in this lesson.

If we want to put our event handlers for our Cookie Recipe project into a JS file, it's a matter of creating a file and doing just that. In the following example, I've created a scripts.js file in a js/ directory in my Cookie Recipe project, and I've taken the 3 mouseover event handlers and placed them directly inside:

// User Interface Logic

let h1 = document.querySelector("h1");

h1.onmouseover = function() {

window.alert("I am a heading element.");

};

let p = document.querySelector("p");

p.onmouseover = function() {

document.querySelector("p>em").innerText = "Don't be surprised";

};

let img = document.querySelector("img");

img.onmouseover = function() {

img.style.height = "700px";

};

Notice that I've included a comment to denote the section of my scripts that includes user interface (UI) logic. Any code that you write that accesses the DOM or changes anything in the DOM is considered user interface logic. This is because it interacts with the part of our website that is visible to users: the DOM. If this distinction is still unclear, don't worry — we'll look at more examples of UI and business logic.

Waiting for the Webpage to Load

Let's try this new code out in the browser! After creating the scripts.js file, adding the above code, and reopening or refreshing the Cookie Recipe project in the browser, we're going to see if our mouseover event handlers are working.

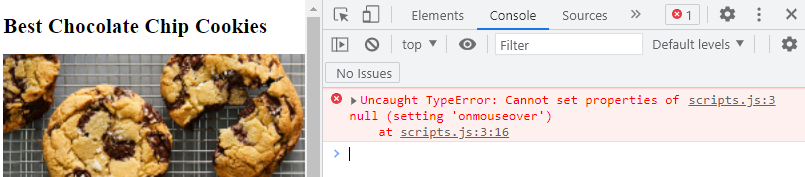

Hmm... it turns out our mouseover events are NOT working. What's going on? When I check the DevTools console, I see an error:

This error says:

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot set properties of null (setting 'onmouseover')

at scripts.js:3:16

Something in my code is null, and it's related to the onmouseover event handler property. I can also see from reading the error message that this error is coming from line 3 of js/scripts.js, which contains this code:

h1.onmouseover = function() { // line 3 starts here.

window.alert("I am a heading element.");

};

According to MDN, a TypeError represents an error that occurs when:

an operation could not be performed, typically (but not exclusively) when a value is not of the expected type.

Given this information, when I reread the error message, I can understand that if there's an issue with setting the property onmouseover on line 3, that must mean that my h1 variable is null. We're getting a TypeError because I can't access a property on a variable that is set to null — there's an issue with the data type. Overall, this is surprising because this same exact code worked in the last lesson when we tried it out in the DevTools console!

It turns out that this is a classic issue that happens when adding JS to a webpage. Because of how our HTML is set up, our JavaScript loads in the browser before our HTML is loaded. How? Check out the snippet of code below from the Cookie Recipe. Notice that the <script> tag that loads our JavaScript in the <head> comes before the <body> with all of the HTML elements that we want to target in our scripts:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title> Best Chocolate Chip Cookies </title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css/styles.css" type="text/css">

<script src="js/scripts.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1 id="specialHeader">Best Chocolate Chip Cookies</h1>

<img src="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2022/02/12/dining/JT-Chocolate-Chip-Cookies/JT-Chocolate-Chip-Cookies-articleLarge.jpg" alt="An image of a cookie"/>

...

</html>

The browser reads our HTML document from top to bottom, which means that the browser loads and processes the JavaScript file first, actually running the contents of our JS file. This happens before the browser gets to the <body> of our HTML to create the DOM. This results in errors from our script file about undefined or null variables. Quite literally, when we're telling our JS to get the H1 element in this code:

let h1 = document.querySelector("h1");

It doesn't exist yet! So, how do we fix this? One option is to put any <script> tags at the end of the body like so:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title> Best Chocolate Chip Cookies </title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css/styles.css" type="text/css">

</head>

<body>

<h1 id="specialHeader">Best Chocolate Chip Cookies</h1>

<img src="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2022/02/12/dining/JT-Chocolate-Chip-Cookies/JT-Chocolate-Chip-Cookies-articleLarge.jpg" alt="An image of a cookie"/>

...

<script src="js/scripts.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Some developers feel strongly about this practice. Others prefer that scripts should stay within the <head> tags, the HTML element that contains all metadata about our HTML document — data that is not displayed and that describes linked resources (files or libraries), the title of the document, the character set, styles, and more. This debate centers around webpage performance — how quickly our webpage can load. We won't get into the details of this now, but you can read more about it on this Stack Overflow article. At Epicodus, we'll always write our JavaScript code in a separate file that we link to in our HTML, so we'll always include any <script> tags within the <head> tags of our HTML documents. So, what's our solution then?

Our web browsers have a window event handler that will allow us to wait until our entire webpage has loaded: window.onload. This event is called the "load" event, and it fires when all of a webpage's dependencies have been fully loaded: images, stylesheets, JavaScript, and the HTML. Just like all of our other event handler properties, we set the value of window.onload to a function:

window.onload = function() {

};

In this case, we're using a function expression.

And what should we put in the body of this function? All of the code that we want to wait to run until our webpage has fully loaded. Or in other words, all of the code that we want to run when our webpage is ready to go. This typically includes setting up event handlers. Let's see how we'll update scripts.js of our Cookie Recipe project to incorporate window.onload:

// User Interface Logic

window.onload = function() {

let h1 = document.querySelector("h1");

h1.onmouseover = function() {

window.alert("I am a heading element.");

};

let p = document.querySelector("p");

p.onmouseover = function() {

document.querySelector("p>em").innerText = "Don't be surprised";

};

let img = document.querySelector("img");

img.onmouseover = function() {

img.style.height = "700px";

};

};

Notice that we've placed all of our onmouseover event handlers directly into the window.onload event handler. This will make it so that none of our onmouseover event handlers get created until after our webpage has been fully loaded. If we re-run our Cookie Recipe project, the error will be gone and we'll find that our mouseover events are working!

Going forward all event handlers that should be created when a webpage loads should be located inside of a window.onload event handler. Take note that you only need ONE window.onload event handler. In other words, multiple event handlers can go inside of the window.onload event handler.

Takeaways

In this lesson, we've learned how to add event handlers to our project's JS file. In the process we learned about the window.onload event handler property and the crucial role it plays in making our JS code wait to execute until our webpage and all of its resources have fully loaded. This resolves the common error of our JS not being able to find the DOM elements it is supposed to target with an event handler. What's actually causing this error is that our JS is being run before the DOM has been constructed, which means the DOM elements actually don't exist when our JS is being run.