📓 2.2.2.6 Working with Multiple Business Logic Files

As our projects get bigger, we'll need to break up our code into multiple files. Doing this — and managing our tests as well as our import and export statements — can be tough for beginners. For that reason, we'll walk through the process by adding functionality for calculating the area of a rectangle to our shape-tracker application.

In the process, we'll use ES6 classes and update our application so the UI can check if three lengths make a triangle and calculate the area of a rectangle. As we add this new functionality, our goal is to keep our code modular and well-organized. The principles we apply here can be used for any number of business logic and test files.

We are adding simple functionality to our application, and it would be easy to just shove the new code into the files we already have. However, that would be a bad move. In the real world, we need to think about scalability. Specifically, how can we make our applications scale up and grow bigger with a minimum amount of pain points? While we should have a general road map for how an application might expand, we can't predict everything the application might need. If it's a successful application, it will likely look very different in five years than it does now. For that reason, we always need to build with an eye on the future.

A helpful analogy for coding with scalability in mind is the process of building an apartment building. If it has a strong foundation, we can add more stories to it in the future. If it has a weak foundation, it will need major overhauls, or worse, we might need to start from scratch, all in order for us to keep building. When an application with a weak foundation starts running into scalability problems, it can lead to major headaches for businesses even just a year later — pain points, wasted developer time, less time spent on new features that users want right now. And if competitors are already building those features while problems arise for the users on our app, they will quickly desert the application.

It's a fact that modular code scales better and is easier to read. When code is modular, we can fix individual units, or modules, of code without disrupting the whole application. There are fewer issues with global scope and fewer bugs. Developers can work more efficiently on different parts of the codebase, and they'll be able to communicate better, too.

Project Structure

We already have most of the files we need. Because we're only adding a small amount of functionality, we'll just need two new files. We'll also add a new directory to house all of our js business logic, because it's always better to organize our code in directories.

src/js/rectangle.js: This will contain the business logic for aRectangleclass.__tests__/rectangle.test.js: This will contain the test suite for tests related to theRectangleclass.

Add the new js directory and the two new files to the project now.

Also, don't forget to move triangle.js into the js directory. We don't need to add index.js to the js directory, because it's our entry point file.

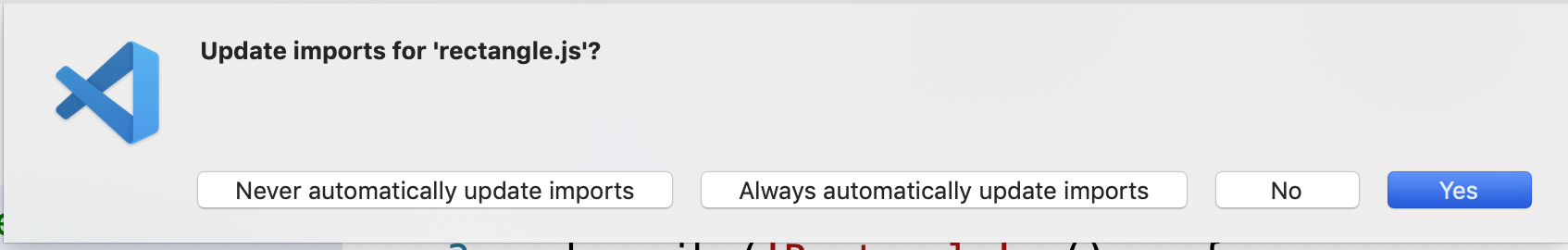

VS Code has a handy little feature where it can automatically update any import statements in the code for you. Here's an example of the prompt (though this one is for rectangle.js).

If you want to do it manually (or VS Code doesn't automatically update the import statements), the relative path for the triangle.js import statement in triangle.test.js looks like this:

import Triangle from './../src/js/triangle.js';

We'll update import statements in the UI logic (index.js) later in this lesson.

Updating to ES6 Classes

Before we move on, let's update the code in triangle.js to use ES6 classes:

export default class Triangle {

constructor(side1, side2, side3) {

this.side1 = side1;

this.side2 = side2;

this.side3 = side3;

}

checkType() {

if ((this.side1 > (this.side2 + this.side3)) || (this.side2 > (this.side1 + this.side3)) || (this.side3 > (this.side1 + this.side2))) {

return "not a triangle";

} else if ((this.side1 !== this.side2) && ((this.side1 !== this.side3)) && ((this.side2 !== this.side3))) {

return "scalene triangle";

} else if ((this.side1 === this.side2) && (this.side1 === this.side3)) {

return "equilateral triangle";

} else {

return "isosceles triangle";

}

}

}

Because we've made a code update, we should verify that our tests still pass. And they do. Thanks to our tests, we can be assured that everything is still working correctly after refactoring our code.

Writing and Passing Our First Test

Because we are using a test-driven approach, our next step is to write a test. We'll start with a test for a Rectangle constructor:

import Rectangle from '../src/js/rectangle.js';

describe('Rectangle', () => {

test('should correctly create a rectangle object using two sides', () => {

const rectangle = new Rectangle(3,5);

expect(rectangle.side1).toEqual(3);

expect(rectangle.side2).toEqual(5);

});

});

Because a rectangle has two pairs of sides, each with equal length, we'll only need to pass in two sides as parameters.

Next, we'll run $ npm run test to fail our test. As expected, this test will fail, but it should be clear by this point that it's a bad fail:

TypeError: _rectangle.default is not a constructor

There's no constructor yet! Let's add just enough code to have a good fail.

export default class Rectangle {

constructor() {

}

}

We just add and export a Rectangle class with an empty constructor. Now when we run $ npm run test, we'll get a good fail:

expect(received).toEqual(expected) // deep equality

Expected: 3

Received: undefined

With this fail, we've reached our expectation and we know our code is properly wired up.

Next, let's get the code passing by adding parameters and statements to our constructor:

export default class Rectangle {

constructor(side1, side2) {

this.side1 = side1;

this.side2 = side2;

}

}

Let's run our tests again, and we'll find that everything is passing.

By the way, note that we use the same parameters as we do for triangles (side1 and side2). Imagine, for a moment, the havoc that would occur if these variables were globally scoped. It's very common to reuse variable and property names. Thankfully, we can scope them locally.

Next, we'll need to write a test for our only method:

import Rectangle from '../src/js/rectangle.js';

describe('Rectangle', () => {

...

test('should correctly get the area of a rectangle object', () => {

const rectangle = new Rectangle(3,5);

expect(rectangle.getArea()).toEqual(15);

});

});

If we run our tests now, we'll get a bad fail:

TypeError: rectangle.getArea is not a function

Our new method doesn't exist yet — of course testing something that doesn't exist will result in a fail, and a bad one. We'll add the scaffolding for a getArea() method to get a good fail:

export default class Rectangle {

constructor(side1, side2) {

this.side1 = side1;

this.side2 = side2;

}

getArea() {

}

}

When we run $ npm run test again, we'll get a failure message that lets us know that our expectation statement has been reached:

expect(received).toEqual(expected) // deep equality

Expected: 15

Received: undefined

That's much better! Finally, let's add the code to get the test passing:

...

getArea() {

return this.side1 * this.side2;

}

...

With this code in place, we can run $ npm run test and all our tests will be passing.

DRYing Up Our Tests

We should always look for an opportunity to refactor our code. Our source code looks fine but we can DRY up our tests a bit because we are using some repeated code: const rectangle = new Rectangle(3,5);. If we were to build out our code further and add more tests, it would be nice to have a reusable rectangle. This also gives us an opportunity to practice using Jest's beforeEach() function in our code. Here's the updated tests refactored to use beforeEach():

import Rectangle from '../src/js/rectangle.js';

describe('Rectangle', () => {

let rectangle;

beforeEach(() => {

rectangle = new Rectangle(3,5);

});

test('should correctly create a rectangle object using two sides', () => {

expect(rectangle.side1).toEqual(3);

expect(rectangle.side2).toEqual(5);

});

test('should correctly get the area of a rectangle object', () => {

expect(rectangle.getArea()).toEqual(15);

});

});

Updating the UI

Now that we have all tests passing, we're ready to update our UI. As we mentioned earlier in the lesson, index.js is not in our src/js directory — it's in src because it's our entry point file.

import 'bootstrap';

import 'bootstrap/dist/css/bootstrap.min.css';

import './css/styles.css';

import Triangle from './js/triangle.js';

import Rectangle from './js/rectangle.js';

function handleTriangleForm() {

event.preventDefault();

document.querySelector('#response').innerText = null;

const length1 = parseInt(document.querySelector('#length1').value);

const length2 = parseInt(document.querySelector('#length2').value);

const length3 = parseInt(document.querySelector('#length3').value);

const triangle = new Triangle(length1, length2, length3);

const response = triangle.checkType();

const pTag = document.createElement("p");

pTag.append(`Your result is: ${response}.`);

document.querySelector('#response').append(pTag);

}

function handleRectangleForm() {

event.preventDefault();

document.querySelector('#response2').innerText = null;

const length1 = parseInt(document.querySelector('#rect-length1').value);

const length2 = parseInt(document.querySelector('#rect-length2').value);

const rectangle = new Rectangle(length1, length2);

const response = rectangle.getArea();

const pTag = document.createElement("p");

pTag.append(`The area of the rectangle is ${response}.`);

document.querySelector('#response2').append(pTag);

}

window.addEventListener("load", function() {

document.querySelector("#triangle-checker-form").addEventListener("submit", handleTriangleForm);

document.querySelector("#rectangle-area-form").addEventListener("submit", handleRectangleForm);

});

There are a few key things to note:

- We

importbothTriangleandRectangleat the top of the file. As our projects grow in size and our UI needs access to more business logic files, we'd add more import statements here. - When we append the result to our P tags, we use template literals to include a message.

Let's also add a new form for calculating the area of a rectangle.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Shape Tracker</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>Enter three lengths to determine if they can make a triangle.</h3>

<form id="triangle-checker-form">

<label for="length1">Enter a number:</label>

<input id="length1" type="number">

<label for="length2">Enter a number:</label>

<input id="length2" type="number">

<label for="length3">Enter a number:</label>

<input id="length3" type="number">

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

<ul id="response"></ul>

<h3>Enter the lengths of a rectangle's two sides to determine its area.</h3>

<form id="rectangle-area-form">

<label for="rect-length1">Enter a number:</label>

<input id="rect-length1" type="number">

<label for="rect-length2">Enter a number:</label>

<input id="rect-length2" type="number">

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

<ul id="response2"></ul>

</body>

</html>

And that's really it! It's not a fancy UI but everything is wired together correctly. Most importantly, this lesson should provide a clearer picture of how we can have multiple business logic files working with our UI and tests.

Remember, whenever a file needs access to a function, class, or some other code from another file, we just need to use import and export statements. We can use these in any JavaScript file. For instance, we might have a business logic file that imports a function from another business logic file. In that case, import and export statements are applicable in the exact same way.

As you build out a bigger project, take the time to break up your business logic into smaller, more modular files and then use import and export statements as needed; webpack will take care of the rest!

Below is a repository for the complete project.

Example GitHub Repo for Shape Tracker

Make sure to use the branch titled 3_multiple_business_logic_files as your point of reference. As needed, review the lesson on accessing code from different branches.