📓 2.1.0.4 Constructors and Prototypes

In this lesson, we're going to explore how JavaScript uses constructors as blueprints for the creation of many new objects of the same type, and prototypes for adding properties and methods to objects.

Let's start by taking a look at how we can use constructors with built-in JavaScript objects.

Constructors

The MDN documentation for strings covers 4 ways to create a string:

Strings can be created as primitives, from string literals, or as objects, using the

String()constructor:

const string1 = "A string primitive";

const string2 = 'Also a string primitive';

const string3 = `Yet another string primitive`;

const string4 = new String("A String object");

We haven't yet learned about using backticks for strings (the third example), and we won't worry about that for now. (Of course, you are welcome to explore this on your own.) What we're interested in is using the String() constructor like we see in the very last example. String() is a constructor function that allows us to create string objects. A constructor is a function that can be invoked using the new keyword to create new objects of a specific type.

We often say that the constructor function is the blueprint for a type of object. A blueprint is a design of something, but notably not the thing itself. This is true for constructor functions. When we create a constructor function, we are defining what the object should look like, meaning what properties and methods it should have.

Then, when we call (invoke) the constructor function, we're asking it to create an actual object that looks exactly like the blueprint. This is just what we're doing when we use the String() constructor function — we're creating a string that has access to all of the properties and methods that strings should have:

> const string4 = new String("A String object");

> string4.toUpperCase();

"A STRING OBJECT"

> "This is " + string4.toLowerCase() + ".";

"This is a string object."

Previously, we have created strings simply by adding quotes " " around the characters we want to identify as strings. This is called literal notation. It triggers JavaScript to create a string primitive, which JavaScript then implicitly converts into an object so that it can have access to properties and methods, like String.prototype.charAt().

When JavaScript turns the string primitive into an object, it does so using the String() constructor function. This process is true for every primitive that JavaScript implicitly turns into an object. To understand this process more in depth, visit this documentation on primitive wrapper objects.

To visually identify constructor functions, they are conventionally named with a capitalized first letter. For example, these are the constructor functions for strings, numbers, and booleans:

// using constructor functions

> const myCodeSchool = new String("Epicodus");

> const myFavNumber = new Number(22);

> const doILikePuppies = new Boolean(true);

The constructor functions for String(), Number(), and Boolean() are not just for JavaScript to use under the hood — we can also use them directly in our code! That said, it is not a common practice. Generally speaking, if an object can be created with literal notation, it is usually easier and more common to use literal notation to create an object of that type.

// using literal notation

> const myCodeSchool = "Epicodus";

> const myFavNumber = 22;

> const doILikePuppies = true;

So when might we use a constructor function?

When to Use Constructor Functions

Almost every built-in JavaScript object has a constructor function that we can use to create an object of that type. One notable exception is the Math object). In many cases, we can only create a specific type of object by using its constructor function. Some examples include:

You may not have worked with the above objects before, and you don't have to start now! These are just examples if you want to explore more.

In this section, we'll spend most of the time focusing on how to create constructor functions to define the blueprint of a custom object. We'll then learn how to call on this constructor function to create multiple objects of that same type.

Before we get into that, let's learn a bit more about how to use constructor functions for built-in JavaScript objects.

Using a Constructor Function

Let's use the String() constructor function to create a new string. Put the following code into the DevTools console:

> let testGreeting = new String();

undefined

> testGreeting;

String {" "}

length: 0,

[[Prototype]]: String,

[[PrimitiveValue]]: ""

The testGreeting variable has been set to a String object with an empty string inside of it. To see the properties of this object, we expand it in the DevTools console by clicking the arrow to the left of String {" "}.

Now try this out:

> let testGreeting2 = new String("Hello!");

undefined

> testGreeting2;

String {"Hello!"}

0: "H",

1: "e",

2: "l",

3: "l",

4: "o",

5: "!",

length: 6,

[[Prototype]]: String,

[[PrimitiveValue]]: "Hello!"

In both of these examples, we see the String() constructor is called with the new keyword, and it returns a string object. These objects have 3 properties: length, [[Prototype]], and [[PrimitiveValue]]:

lengthlists the number of characters in a string. Note that this property isn't included for every built-in JavaScript object. For example, numbers do not have alengthproperty, but arrays do.[[Prototype]]points to the object's blueprint. In this example, we can seeStringlisted as the value, which means thetestGreetingandtestGreeting2objects were both created from the blueprint for theStringobject type. Note that you can expand the[[Prototype]]property and you'll see a list ofStringproperties and methods. As we'll learn later, JavaScript objects share functionality through prototypes.[[PrimitiveValue]]lists the value of the corresponding primitive. This only exists for JavaScript primitives that are turned into objects, which includes all primitives except fornullandundefined.

If we wanted to access these properties, we'd do so like this:

// length

> testGreeting2.length;

6

// [[Prototype]]

> testGreeting2.__proto__;

String {'', constructor: ƒ, anchor: ƒ, big: ƒ, blink: ƒ, …}

// [[PrimitiveValue]]

> testGreeting2.valueOf();

"Hello!"

These same properties can be found on a string primitive that we create with literal notation, and that JavaScript then implicitly turns into an object. Let's see how this works. First, we'll create a string:

> const myStr = "Hello!";

undefined

Then we'll access the number of characters in the string through the length property:

> myStr.length;

6

To access the [[Prototype]] property of myStr, we'll access the __proto__ property:

> myStr.__proto__;

String {'', constructor: ƒ, anchor: ƒ, big: ƒ, blink: ƒ, …}

To access the primitive value of the string, we use the String.prototype.valueOf() method:

> myStr.valueOf();

"Hello!"

It may seem odd to access the primitive value of myStr, a variable holding a primitive value, but what's happening here is that String.prototype.valueOf() is accessing the primitive value of the string object that myStr is turned into. If that feels confusing, well, that makes sense. The whole process of changing primitives into objects happens out of sight, which makes that process harder to understand. For better or worse, with some JavaScript you just have to accept that that's how it works.

Array-Like Objects

There's one more thing to note about the string object that's returned from he String() constructor: it is an array-like object. To understand this, let's revisit our testGreeting2 example:

> let testGreeting2 = new String("Hello!");

undefined

> testGreeting2;

String { Hello! }

0: "H",

1: "e",

2: "l",

3: "l",

4: "o",

5: "!",

length: 6,

[[Prototype]]: String,

[[PrimitiveValue]]: "Hello!"

Notice that for testGreeting2, when we provided the value "Hello!" as the argument, the constructor creates properties for the index positions of each character. These properties allow us to use bracket notation to access the characters in a string by their index locations:

> testGreeting2[0];

"H"

> testGreeting2[5];

"!"

Objects that are set up with numbers as their property keys to represent an index location are called array-like objects. We first encountered array-like objects in the "Arrays and Looping" course section when we worked with the Web API objects NodeList and HTMLCollection, which are both objects that contain a collection of HTML element objects. These objects are returned from calling methods like document.querySelectorAll() or document.getElementsByClassName().

There's a couple things to note here. First, take note that while the property keys look like numbers, they are actually strings. This is another situation when JavaScript is not intuitive. Just remember that object keys in JavaScript are always strings.

Also note that not every constructor function returns an array-like object! Only some do. If you encounter an object that has (what seems like) numbers as property keys that start at 0 and increment by one, then you are working with an array-like object.

Object Types versus Object Instances

Let's review the difference between object types and object instances. This will help us when we begin creating our own custom object types.

When we've talked about the variable testGreeting2 we've described it as an object of a specific type:

> let testGreeting2 = new String("Hello!");

We've also talked about how the constructor function String() creates objects based on a blueprint or template for an object type. Well, the technical terminology to describe these is as follows:

- Object type or just type: The type of an object defines what data it contains, including all of the properties and methods that an object of that type has in it. In other words, the object type is the blueprint or template for creating an object, but not an actual object. With the examples we've seen so far,

Stringis a type, andString()is the constructor function for that type, whereastestGreeting2is an actualStringobject. Notice that the constructor function and the type have the same name! This is by convention.- Note that you'll also see the terminology class if you are exploring constructor functions on MDN. A class is simply an object type, and in JavaScript we can create an object type by using class syntax. In a later course section, we'll learn how to use class syntax.

- Object instance: An instance or "object instance" is an actual object of the same type as the constructor that made it. In our recent example

testGreeting2is an instance of theStringtype. Object instances have the properties and methods that are described in their corresponding type. For example, this means thattestGreeting2has the string methods likeString.prototype.concat()andString.prototype.toUpperCase().

Important Takeaways So Far

Whew! We just covered a lot of new information, some of which is more important than others. So, let's refocus on the important takeaways about constructors:

- JavaScript uses constructor functions to make an object of a specific type:

- The object type lists all of the properties and methods that every object instance has; it is like a blueprint or template that we can create instances of objects from.

- An object that's created from a constructor function is called an instance, or object instance.

- The first letter of JavaScript constructor functions are capitalized. The naming for constructor functions follows UpperCamelCase.

- The name of the constructor function always matches the name of the object type.

- Almost every built-in JavaScript object has a constructor function. While it's not common to use constructor functions to create primitives, we can do that, just like with saw with strings.

- The properties and methods that we can access through a string object created with a constructor function are the same properties and methods that we can access in a string primitive. This reminds us that JavaScript turns all primitives into objects, except for

nullandundefined.

If you are feeling unsure about some of the topics or concepts that we've covered, don't worry — we'll revisit all of this information as we continue in this course section and we'll have a lot of chance to practice.

Next, let's create a custom object type and constructor of our own, and solidify these concepts.

Creating a Custom Constructor Function and Object Type

Let's turn back to our original scenario of using constructors to streamline the process of tracking dogs for a dog walker. We'll need to track multiple dogs, and for each dog we'll be tracking the same properties: name, colors, and age. The only difference from dog to dog will be in the values for those properties. Because of this, we can use a blueprint to base every dog off of. Rather than repeating all of the code for each dog in separate object literals, we'll make a constructor function that we can use over and over again.

Below is the constructor function for the Dog object type. Here, we're using the constructor function to define what properties the Dog object type should have in it. We can see in the following example that every dog object we create will have name, colors, and age properties. Let's put this code into the DevTools console:

> function Dog(dogName, dogColors, dogAge) {

this.name = dogName;

this.colors = dogColors;

this.age = dogAge;

}

When we call the constructor function Dog(), it will create a new instance of the dog object based on the arguments that we pass in:

> let myPuppy = new Dog("Ernie", ["brown", "black"], 3);

> myPuppy;

Dog {name: 'Ernie', colors: Array(2), age: 3}

We must pass in an argument for every parameter in the constructor function, otherwise, we'll end up with undefined values in our dog object.

We can access the name of the new dog:

> myPuppy.name;

"Ernie"

The colors of the new dog:

> myPuppy.colors;

["brown","black"]

And its age:

> myPuppy.age;

3

Remember, the myPuppy object here is an instance of the Dog object type.

A constructor is the blueprint that specifies how to create an object of a specific type. You can think of the Dog constructor here as a factory that can be used repeatedly to build a bunch of dog objects, using the constructor as a blueprint.

This means that we'll always have one Dog object type that is defined by a constructor, with potentially many instances of that type. Let's create 3 more dogs:

// instances of the Dog object type

> let falcor = new Dog("Falcor", ["black"], 4);

> let nola = new Dog("Nola", ["white", "black"], 6);

> let patsy = new Dog("Patsy", ["brown"], 7);

And each of these Dog object instances all have a name property, a colors property and an age property. For example:

> falcor.name;

"Falcor"

> nola.name;

"Nola"

> nola.age;

6

> patsy.colors;

["brown"]

> patsy.age;

7

Now, we know how to create custom objects with properties, but what about methods? Let's take a look at how to add methods for both JavaScript's String type and our custom Dog type next.

Prototypes

To share functionality between objects, JavaScript uses prototypes. A prototype is an object that contains the functionality of a specific object type that is added as a property to the object we're working with. Let's look at an example to make this new information concrete. Do you remember the [[Prototype]] property on the string object we created?

> let testGreeting2 = new String("Hello!");

undefined

> testGreeting2;

String { Hello! }

0: "H",

1: "e",

2: "l",

3: "l",

4: "o",

5: "!",

length: 6,

[[Prototype]]: String,

[[PrimitiveValue]]: "Hello!"

Well, [[Prototype]] is the property that stores the prototype object for testGreeting2. If we want to access the [[Prototype]] property, we need to do it via __proto__:

> testGreeting2.__proto__;

String {'', constructor: ƒ, anchor: ƒ, big: ƒ, blink: ƒ, …}

So what does this tell us? testGreeting2 is an instance of the String object type, and because of this, testGreeting2 inherits functionality from the String object type. This inherited functionality is stored in the [[Prototype]] property, which we access through __proto__. In practical terms, this means that any of the string methods we use on testGreeting2 are actually inherited from its prototype, the String object type.

This means that any string methods that we call on testGreeting2 are actually defined in the prototype object:

> testGreeting2.toUpperCase();

"HELLO!"

> testGreeting2.charAt(2);

"l"

> testGreeting2.includes("ll");

true

When we call any of these methods, what happens is JavaScript first looks in the instance object (testGreeting2) to find those methods, and if it can't find them there, JavaScript then looks to the __proto__ property to find them in the prototype object.

So, all instances that we create with the String constructor inherit from the String.prototype object. In fact, every object we create inherits functionality from a prototype object. (We'll see more examples soon!)

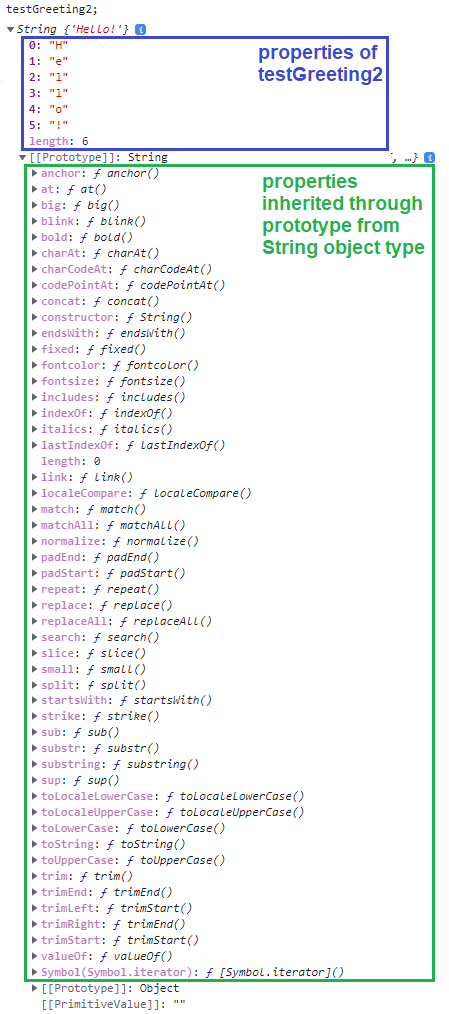

Note that we can explore this prototypal inheritance in the DevTools as well. In the following image, the blue square highlights the properties that belong to testGreeting2 (the string instance) and the green square highlights the properties that testGreeting2 inherits from the String object type.

Prototypal inheritance is what allows every string we create (with or without the constructor function) to have access to the same set of methods. Note that we can also add to the prototype object!

Let's add a custom method to String.prototype:

> String.prototype.addExcitement = function() { return this + "!!!!!!!!!" };

ƒ () { return this + "!!!!!!!!!" }

> testGreeting2.addExcitement();

"Hello!!!!!!!!!!"

As soon as the new method is added, all current and future strings (or more technically, "instances of the String type") will have access to it. Now I can run testGreeting2.addExcitement() and get Hello!!!!!!!!!.

If I create a new string, it, too, will have access to the prototype's addExcitement method:

> let newGreeting = "Hola";

undefined

> newGreeting.addExcitement();

"Hola!!!!!!!!!"

We might think, why aren't methods just added to the constructor instead of to a prototype object that all object instances inherit? Well, the prototype object allows us to define functionality like a method once, and then all instances of that object type automatically have access to it.

On the other hand, if we added all string methods to the String constructor, then every new string we create would have a new instance of every method. For example, if we created three strings, we'd have 3 copies in memory of the toUpperCase() method. By adding toUpperCase() to the prototype object with String.prototype.toUpperCase(), this method is created only once in memory and shared by all of the string instances, and this is more efficient.

Also, while we can directly modify JavaScript object types (such as by adding methods to String.prototype), generally it's a bad practice. We should always add methods to our own custom object types — otherwise, built-in JavaScript object types in our applications will have unexpected functionality that could be hard for other developers to navigate and debug.

Adding Methods to the Dog Prototype

Let's look at our Dog type again. We can add our original methods to Dog.prototype so that all dogs have these behaviors available to them.

> Dog.prototype.speak = function() {

console.log("Woof!");

};

ƒ () {

console.log("Woof!");

}

> Dog.prototype.humanYears = function() {

return this.age * 7;

};

ƒ () {

return this.age * 7;

}

Note the semicolons here, by the way. Why are we adding semicolons when we are defining functions? Well, we are using assignment to assign a function to a property. It's somewhat similar to when we assign a value to a variable, so we use semicolons.

myPuppy can now speak:

> myPuppy.speak();

Woof!

We can also have its age calculated in human years:

> myPuppy.humanYears();

21

And, every new dog will also have these methods:

> let newPuppy = new Dog("Goliath", ["gray"], 2);

undefined

> newPuppy.speak();

Woof!

> newPuppy.humanYears();

14

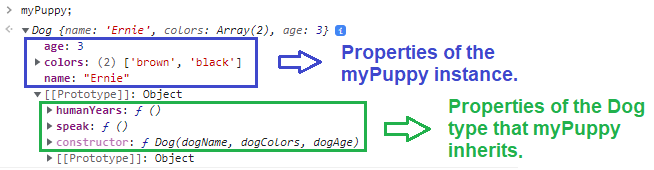

Just like we did with the string testGreeting2, we can view the properties of myPuppy in the DevTools console, and see which ones are inherited through the prototype object and which belong to the instance:

We can also access the prototype object through the __proto__ property:

In summary, every time we create a new dog using the new keyword, it calls the Dog() constructor, which provides the blueprint for creating an instance of the Dog type, giving it certain properties. The new instance of the Dog type also automatically gains access to all methods defined on the shared Dog prototype.

Also, we choose to add methods to the prototype of an object type so that we can define the method once, which saves memory and is more efficient.

Prototype Chain

In JavaScript, all objects inherit functionality from at least one other object, which ultimately derives its functionality from the Object type. How does this work? Every object has a prototype property (accessed through __proto__) that is a link to another object. This creates a prototype chain and is the mechanism by which one object inherits from multiple other object types. Let's work through some examples of this.

Before we jump in, let's review what the Object type is. Do you remember that JavaScript data types are divided into two categories, primitives and objects? Well the Object type corresponds to objects, a foundational data type in JavaScript. We can create an object with literal notation or with the Object() constructor function. In the following example, we're creating two empty objects:

> const myObj = {};

{}

> const myOtherObj = new Object();

{}

Being familiar with the Object type is important, because all JavaScript objects of any and every type inherit functionality from the Object type. The Object type is the most generalized object, and all other object types are more specific variations. With that in mind, let's get into examples of the prototype chain!

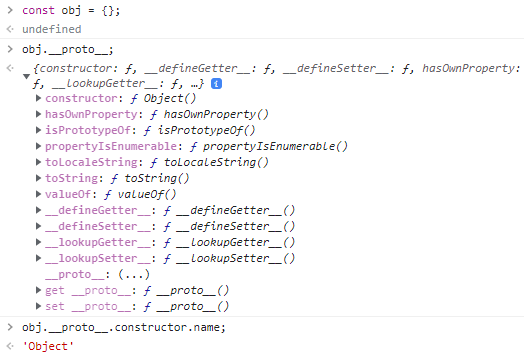

In this first example, we'll see that an object literal gets its functionality from the Object type:

Note, too, that we can confirm the name of the constructor for our object obj by entering the following:

> obj.__proto__.constructor.name;

"Object"

And remember that the name of a constructor matches the name of the object type. This confirms that obj inherits from the Object type.

If an object inherits functionality from the Object type, what does Object inherit its functionality from? We can move up the chain of prototypes by simply accessing the next __proto__ property: obj.__proto__.__proto__;. Let's try entering that into the console:

Notably, we get null returned to us. So, what does this mean? Well, when we get null returned from accessing a __proto__ property, it means we've reached the end of the chain of inheritance.

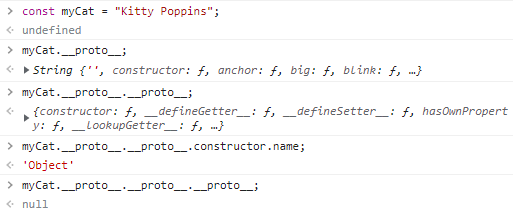

Let's see another example with a string. As we'll see, an instance of a string inherits from the String object type, which itself inherits from the Object object type. In the following example, we'll use a string literal.

There's a couple things to note in the above code snippet:

- We access the

__proto__property 3 times: once formyCat, once forString, and once forObject. The__proto__property forObjectalways returnsnull, which indicates that we've hit the end of the chain of inheritance. - It's easy to tell that

myCatinherits fromString, but harder to tell thatStringinherits fromObject. To doubly confirm, we inputtedmyCat.__proto__.__proto__.constructor.name;which tells us the name of the constructor for that object type, which is"Object", and this confirms thatStringinherits fromObject. This confirmation process works, because the name of a constructor function always matches the name of the object type.

Now let's try this same process of accessing the chain of inheritance for our Dog object. Similar to the example with the string, we'll see that an instance of the Dog type (myPuppy) inherits from the Dog object type, which itself inherits from the Object object type, which itself does not inherit from anything and ends the chain of inheritance.

![This image shows the result of doing the following: (1) creating a dog object with `let myPuppy = new Dog("Ernie", ["brown", "black"], 3);`, (2) chaining and accessing `__proto__` properties, first with `myPuppy.__proto__`, then with `myPuppy.__proto__.__proto__`, and finally with `myPuppy.__proto__.__proto__.__proto__`. This shows how `myPuppy` inherits from `Dog`, which inherits from `Object`.](/assets/images/dog-chain-of-inheritance-17d4acac6d05911e2434da8b48089f67.png)

Summary

We've covered a lot of new information in this lesson, and some of it has involved looking under the hood of JavaScript, which isn't always easy. If you are feeling overwhelmed, that's a normal reaction. Don't worry — we'll get a chance to practice a lot with constructors and prototypes in this section, and we'll continue using these in future sections as well.

Here's a summary of the important concepts we covered in this lesson:

- JavaScript objects inherit functionality from other objects through prototypal inheritance.

- A prototype is just an object that lists properties that another object inherits.

- There's a chain of inheritance by which an instance of an object, like a string or a dog object or a number, inherits from multiple other objects. We can view this inheritance chain by accessing the

__proto__properties. We know we've reached the end of the prototype chain when we getnullreturned to us. - We choose to add methods to the prototype of an object type so that we can define the method once, but all object instances still have access to that method. This saves memory and is therefore more efficient. This is in contrast to adding a method to the constructor. In this case, when an instance of an object is created so is a new instance of that method (and any other properties), which takes up more memory.

- Using a constructor function or literal notation creates an instance of an object type based on two things: the properties that are defined in the constructor function and what's added to the prototype object for that object type.

- The name of a constructor function always matches the name of an object type.

- An instance of an object is stored in a variable and is an actual object, while the object type is the blueprint that defines all of the properties an object of that type should have.

Generally speaking we won't be accessing the __proto__ property a lot when we're writing our code. However it is really helpful to understand how to access the prototype object in order to actually see how JavaScript's prototypal inheritance works!

More Resources

Note that we've just covered the basics of prototypal inheritance. As always, there's more to learn! Further exploration is optional, but if you are interested in learning more, we recommend these resources: